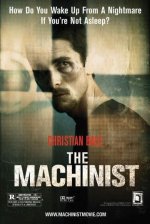

Imperialist decadence and schizophrenia: the example of

"The Machinist"

"The Machinist" (http://machinistmovie.com/)

(http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0361862/)

Directed by Brad Anderson; written by Scott Kosar

Paramount Classics

R / Norway:15

2004

Reviewed by a contributor November 29, 2004

While it might encourage some gender oppressors to question their hypocritical attitude towards child abusers and other perpetrators of crimes against children, and to question their own patronizing attitude towards children, "The Machinist" obscures the oppression of children under patriarchy by focusing on a particular possible effect of children's oppression under patriarchy (adults' perpetrating hit-and-runs against children), misrepresenting the causes of adults' violent crimes against children in general, and failing to illustrate what children have in common as children and gender-oppressed people.

The violence, and even the sex, in "The Machinist" are genuinely uncomfortable to watch and not enjoyable, which may be a redeeming value of the movie in the context of reactionary movies with violence that is enjoyable or intoxicating. Although the main character's difficult-to-sort-out perceptions and misperceptions are part of the script, "The Machinist" misleadingly blurs the distinction between consciousness and objective reality, and even the distinctions among dreams, fantasies, hallucinations, illusions, and memories, but the movie usefully illustrates some aspects of intimacy and sex work in oppressor nations (while ignoring conditions in the same areas in oppressed nations).

Also, "The Machinist" serves as an example of how the movies are reflecting parasitic, urban oppressor nationalities' angst. Past movie reviews on MIM's Web site have mentioned this angst, and this review explores some aspects of the topic a little bit more. A schizophrenic-like mental formation arises out of imperialist-country parasites' experiencing an objective and subjective contradiction between the powerfulness of their parasitic privileges and their powerlessness at the level of lifestyle. This formation appears in the movies as what is commonly understood as angst. Noirish movies featuring bourgeois workers, like "The Machinist," often resonate with potentially fascist workers' sentiments through this juxtaposition of u.$. "middle-class" or "working-class" angst and urbanism.

Subtlety in "The Machinist"

I went to see "The Machinist" on a tip, knowing barely anything about the movie except what I gleaned from a trailer.(1) Based on the trailer, I expected to see a movie artistically and politically similar to "Saw" (2004) , which is more of a discomforting caricature of sadistic "reality TV," but featuring the "working" white man this time and one grotesquely thin, possibly drugged-out Euro-Amerikan man's experience of being tormented by a mysterious predator and living a contradictory parasitic life in an imperialist-country metropolis propelled and shaped by forces beyond his individual control. Like the plain title of Sergei Eisenstein's "Strike" (1925) , the alluringly nondescript title of "The Machinist" almost demands Marxists' attention. There was "The Pianist" (2002). Before that, there was "The Mechanic" (1972). Now, there is "The Machinist." At first glance, gloomy and gritty "The Machinist" seems to be concerned with depicting the alleged sufferings of the white working class in the united $tates. The very title of " The Machinist" seems to blur the distinction between exploitive workers in imperialist countries, and proletarians, or put skilled workers in the emotive limelight of the persecuted and victimized.

Given "The Machinist"'s potential for popular appeal based on both artistic and political criteria, I was surprised to find myself sitting among the oh-so effete or "alternative" bourgeois connoisseurs of foreign/international movies, independent movies, and "ethnic" movies set in places like feudal China (for example, "House of Flying Daggers," 2004) and idyllic Western European countries. In fact, "The Machinist" opened in limited release on October 22, 2004, in the united $tates and has shown largely in those artsy, "sophisticated" independent theaters. If the average movie ticket price is $6.25, then fewer than 100,000 people have seen "The Machinist" in Kanada and the united $tates so far.

Despite the foreign movie trailers that appeared before the main feature, Barcelona-based Filmax's "The Machinist" is set in an unidentified city in the united $tates. Whether because of the filming of the movie in Barcelona or because of intentional obscuring of the city's identity, there seems to be nothing distinctive about the city except the Amerikan cars, the spoken and written English language, the different Kalifornian accents, and so on. The main character Trevor Reznik (Christian Bale) is a gaunt, sickly-looking white man who works in a machine shop as a lathe operator. He regularly visits a call girl and spends a hundred dollars on her all at once. He pays very big tips to Marie (Aitana Sánchez-Gijón), an airport café or restaurant waitress who serves him pie at the counter.

A flash-forward at the beginning of the movie shows Trevor, frustrated, trying to dump what appears (to Trevor) to be a body wrapped in a rug. Later in the movie, Trevor becomes fearful after hangman game sticky notes--with spaces for six letters, two of which are mysteriously written in later--seem to suddenly appear on his refrigerator door. There seems to be someone playing mind games with him.

Plot-wise, the ball starts rolling after Trevor, distracted with staring at someone who appears to be an another, informally, irregularly employed lathe operator, accidentally switches on a lathe machine and causes Trevor's coworker Miller (Michael Ironside) to lose a forearm. While Trevor is explaining the accident to company bosses and officials, who already suspect that Trevor may be a drug addict because of his weight, there is a sign that Trevor is having hallucinations. The bosses and officials deny that Ivan (John Sharian) even exists. Trevor continues to believe that Ivan exists and associates Ivan with different people as if each imaginary couple were conspiring against Trevor. In a photograph Trevor apparently steals from Ivan's wallet while sitting at a bar, Trevor sees Ivan together with Trevor's coworker (the obese one with the glasses) whom Ivan was covering for. They were fishing together. Later, Trevor thinks that the photo is proof that Ivan is Stevie's (Jennifer Jason Leigh) boyfriend. [Spoiler warning] It turns out that it is Trevor himself who is really in the picture, literally instead of Ivan, and that Ivan is a figment of Trevor's imagination. Trevor's hanging out with Marie and her son, Nicholas, at a carnival and accompanying Nicholas on a haunted-house-style ride, during which Trevor sees a severed arm and an unrecognizable body lying in a pool of blood, also turn out to be hallucinations of Trevor's. Significantly, during the same carnival ride, Nicholas has what seems to be a seizure accompanied by vomiting, and Trevor defensively tells Marie that he didn't mean to hurt Nicholas.

I talked with someone who described "The Machinist" as being about the social construction of memories in general. Other reviewers have been more specific and acknowledged what is going on with the triad of Trevor, Ivan, and Nicholas. It is pretty straightforward. In pop-Freudian terms, otherwise-compassionate Trevor is so agitated by his hit-and-run that may have killed a child (Nicholas), that Trevor's mind represses memory of the incident out of his consciousness. Trevor's mind converts Trevor's guilt and self-hatred into hatred for another, imaginary persyn (Ivan). Trevor's mind externalizes the object of Trevor's self-hatred. Trevor's image of himself as a criminal and even a predator of children is transferred onto Ivan, whom Trevor, at one point, hallucinates abducting and killing Nicholas.

The imaginary predator Ivan had to have his toes grafted onto his hand to replace fingers that were lost in a workplace accident. Ivan is disfigured, and this contributes to his intimidating, mysterious appearance. Ivan has a ruthless, hatchet-man vibe.

"The Machinist" is so caught up in trying to be subtle for plot reasons and also for subtlety's sake—and oh-so neo-noirish with its desaturated color, grungy toilet sex in a dilapidated bar bathroom, morally ambiguous antagonist-protagonist, petty-bourgeois workers' drudgery, and substance addiction in an oppressor-nation, urban context—that it is difficult to tease out anything more than the superficial Freudian content. In "The Machinist," there is a not-so subtle allusion to Fyodor Dostoyevsky's book The Idiot , but it is likely the case that few viewers will recognize that there is an intended discursive relationship between Prince Myshkin and Trevor Reznik, so there is little point in discussing "The Machinist" in the context of Dostoyevsky's book here. Most viewers will just come away from "The Machinist" with the impression that "The Machinist" is an artsy, somehow-sophisticated movie—either that or an irritatingly incomprehensible movie.

I can't blame some reviewers for saying that "The Machinist" is a comment on memory and perception, in general, as being matters of individual perspective. I would like to say that "The Machinist" is saying something about gender oppression(3) in featuring a child character, but "The Machinist" does not lend itself to the interpretation that Trevor symbolizes gender oppressors who feel guilty about oppressing children.(4) "The Machinist's" take home messages about memory, perception, and perspective, seem to be timeless and universal in the sense of being contextless. It seems that "The Machinist" could have told basically the same story, but with something other than a hit-and-run incident involving a child to give the plot a form.

To the extent that "The Machinist" does encourage some viewers to think about how they benefit from the oppression of children under patriarchy while they pay lip service to the concerns of child murder victims and child abuse survivors, "The Machinist" deserves praise. However, this will happen probably only by accident since "The Machinist" does not really contest the patriarchal stereotype of gender oppressors as psychopathic, violent predators, in other words, something other than "normal" adults; "The Machinist" might make a handful of child abusers feel guilty, and that's it. Quite the opposite, "The Machinist" depicts Trevor as a psychopath who suffers from insomnia, if not schizophrenia. "The Machinist" does nothing to disturb the idea that children's oppression outside of the family is limited the behaviors of some violent psychopaths. In fact, "The Machinist" reinforces this idea through the character of Ivan and even the character of Trevor, who has psychiatric symptoms.

True, otherwise-compassionate, guilt-ridden Trevor, not Ivan, turns out to be the "K-I-L-L-E-R," but imaginary Ivan is how Trevor sees himself.

If "The Machinist" is saying that basically good people can make so-called mistakes (Trevor's hit-and-run), go mad, and repent as Trevor eventually does, then "The Machinist" must be criticized for falsely portraying gender oppression, and particularly the gender oppression of children, as a matter of lifestyle. I hesitate to say that "The Machinist" falsely portrays "gender oppression" because it doesn't actually do that. Instead, it portrays, in a very one-sided and myopic way, a particular possible effect of children's oppression under patriarchy (adults' perpetrating hit-and-runs against children)—while simultaneously and actively reinforcing patriarchal social constructions of childhood. As if it had a massive blind spot, "The Machinist" doesn't even pretend to represent children's common relations under any system. This contradictory duality of false portrayal / non-portrayal of children's oppression under patriarchy is present in almost every memorable movie that features a child character and must have a bearing on the reproduction of children's oppression under patriarchy by means of ideology.

The oppression of children under patriarchy

To say that "The Machinist" portrays the gender oppression as a matter of individual persynal decisions, or psychopathology, implies that the movie actually portrays gender oppression in the first place and in some sense. In fact, it is not clear that hit-and-run injuries suffered by children have anything to do with gender oppression; at least, it is not obvious to most movie viewers, who don't even think about concepts of gender oppression, or patriarchy. So, it would be hard to say that Trevor's leaving the scene of the accident injuring a child is, by itself, sufficient evidence that "The Machinist" depicts gender oppression. Although, it is reasonable to wonder how we got to the point in the movie, culturally and socially, where it is possible for an adult to knowingly leave the scene of a vehicular accident that immobilized a young persyn who has a much smaller body and different resources, standings, and statuses, than most adults.

The reason why it is still possible to talk about "The Machinist" as falsely portraying children's gender oppression in some sense is that the movie inscribes frailty, innocence and vulnerability onto Marie's son, Nicholas, and puts Nicholas in the context of the imaginary psychopathic, violent predator-stranger Ivan. Also, Trevor's experience of déjŕ vu when he seems to take a picture of Marie with Nicholas at the carnival is a result of Trevor's memory of a photo of himself with his mother at the same carnival. It seems that Trevor thinks of himself as a child or being like Nicholas, and pop Freudian psychology would say that both Marie and comforting, soothing Stevie, with her conspicuously nude breasts, are symbols of "the mother." Thus, "The Machinist" purports to represent childhood, but fails to represent, in any way, accurately or inaccurately, children's common relations under any system. Instead, the movie presents a distorted representation of the relationship between child hit-and-run victims and adult perpetrators of hit-and-runs against children without even a distorted representation of the relations that children have in common.

I get no sense that "The Machinist" is trying to say something about children's collective experience under any system, just that "The Machinist" does nothing to disagree with the contemporary social construction of children as being frail, innocent, vulnerable and so on, but even then, Nicholas is unusual in having visible neurological and visual impairments. Just by failing to represent or misrepresent children's commonalities and common relations, and focusing on violent illegal crimes against children without accurately representing their perpetrators (for example, in reality, it is largely the children's parents who commit child abductions and murders), "The Machinist" falsely "portrays" children's oppression under patriarchy.

In the public imagination, the acts called "child abuse" (which excludes the forms of oppression of children that the public finds to be legally tolerable) are caused by moral depravity, psychopathology, and stress. This view is totally blind to how childhood as an institution and relationship under patriarchy causes child abuse. "The Machinist" does nothing to disturb this view, but reinforces it.

Movie violence

A redeeming value of "The Machinist" may be that it is genuinely uncomfortable to watch and may upset people's taste for reactionary movies with gratuitous violence. Although the makers of "The Machinist" apparently tried to make the movie subtle for subtlety's sake in some places, little of the violence in "The Machinist" is comical or enjoyable (in that action or horror movie fan kind of way) with the possible exception of Trevor's moving in front of a moving car, and rolling over its hood, at one point. The acting isn't goofy. The relatively intense gore in "The Machinist" is unexpected.

Prostitution and romantic intimacy

Other reviewers have emphasized the actor Christian Bale's excruciatingly thin physical appearance and expressed worry about the actor's own health. At one point, gangly Trevor flaunts his skinniness as if to disgust Stevie on purpose. It would be interesting to contemplate scenes in movies where the womyn looks out of place in sex with an attractive man. It would probably involve some kind of prostitution relationship where the male plays the prostitute role.Trevor pays money to the call girl Stevie. This isn't surprising, but in another scene, the waitress Marie objects to being tipped for providing Trevor with companionship at the airport restaurant counter. This is all interesting because on the one hand, "The Machinist" could illustrate the fact that white wimmin in the united $tates often engage in sex work for reasons other than subsistence survival (and may be competitive for sex work occupations because of physical attributes), but on the other hand, "The Machinist" could illustrate that other such wimmin participate in not only romantic intimate relationships, but sex work, for free. Marie (who, unlike Stevie, is a figment of Trevor's imagination) eventually starts rejecting Trevor's big tips and says that she would better enjoy Trevor's taking her out on a date. Stevie repeatedly offers Trevor "off the clock" freebies and clearly blurs the distinction between romantic intimacy and sex work by offering to stop hooking so she can be Trevor's girlfriend.

Of course, "The Machinist" undermines itself because it turns out that Marie is a figment of Trevor's imagination. It's as if Trevor were just having patriarchal fantasies. In the case of Stevie, the depiction of old or ugly men with money exchanging it for sex with attractive wimmin is part of what MIM refers to as the eroticization of power.

Trevor's hallucinations

Regarding the hallucinations, which are actually suggested right from the start of the movie, when Trevor washes his hands with skin-burning bleach (and later, "pure lye"—get it, pure lie) to wash away the "blood on his hands," there is the question of whether "The Machinist" is about perception and perspective in general, or not. "The Machinist" seems to purposefully blur the distinction between consciousness and objective reality and even blurs the distinctions among dreams, fantasies, hallucinations, illusions, and memories, reducing them all to amorphous distorted perception. Does Trevor wash his hands with pure lye, or doesn't he? If he doesn't, is Trevor having a dream about washing his hands with pure lye, or is the pure lye purely symbolic and supposed to be visible only to the viewer? (When's the last time you saw a bottle of bleach or lye lying around in a bathroom?) Does Trevor hallucinate the "bleach" labels on the bottles while he is really washing his hands—or imagine them as part of a fantasy while he is really washing his hands? To the extent that "The Machinist" encourages a relativistic outlook by which it is impossible to discern what is true about objective reality, the movie distracts from changing the world and destroying oppressive systems.

Some reviewers have compared "The Machinist" with similarly-themed "Memento" (2000), so maybe these movies portraying relationships among perception, perspective, and psychopathology, represent a new genre in the movies. In any case, we should ask why it is that these movies focus on interpersynal relationships between people with different gender identities, for example, children, men, and wimmin, and why the movies are set in imperialist-country cities or towns.

More likely, what "The Machinist" and similar "noirish" movies about perception and psychopathology represent is a new tendency in movie culture to respond to a certain contradiction of imperialist-country, metropolitan life. This is a contradiction between powerfulness and seeming powerlessness—and actual powerlessness at the sub-reformist level. The contradiction is between the power implied by, and which comes with, imperialist-country parasitism, on the one hand, and the powerlessness, existing at the level of lifestyle, to bend the macro-social forces under the imperialist-patriarchy to an individual parasite's will.

The point here is not to discuss the etiology of insomnia or schizophrenia, at least one of which the character Trevor Reznik seems to have (assuming that either of these is a real illness). Instead, the point is to look at how schizophrenic-like tendencies could develop in persyns' minds as a result of the contradiction between parasitic privileges and seeming powerlessness in imperialist metropoles.

The contradictory life of parasites in imperialist metropoles

That Trevor Reznik comes off as being mentally ill is not controversial. Less clear is why severely underweight Trevor's apparent mental illness coincides with his obvious physical illness. The idea that a persyn might be able to psychosomatically experience the contradiction of parasitic life in imperialist metropoles—containing seemingly impenetrable interior social structure and highly durable buildings and infrastructure, and immersed in larger, seemingly invincible social forces—is interesting from the viewpoint of the gender strand of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism. Mental or physical illness resulting from the power-related contradiction of parasitic life in imperialist metropoles may represent a deterioration or perforation of the ability of imperialist-country gender oppressors to exercise power. This would affect the dynamics of gender struggles within oppressor nations.

The argument here is not that parasitic, urban oppressor nationalities are the only persyns who experience angst (whatever "angst" means), much less that parasitic, urban oppressor nationalities are oppressed in some way; collectively, they are not oppressed in any way. Instead, the spotlight is on these particular exploiters because they are among the audiences of movies showing in the united $tates. This group presents particular problems. For one, for movies to resonate with this group's feelings of impotence or isolation isn't necessarily a good thing in some absolute sense; in fact, it may exacerbate oppressor-nation nationalism if the oppressor-nation parasites viewing the movies don't have any sense of international politico-economic perspective. It is no longer the case that discontent in general is detrimental to capitalism; discontent in oppressor nations is usually channeled into gender- or labor-aristocracy pig fests that further ties them to the exploitive system even as the owners' profit rates decrease. Also, if oppressor nationalities, adults or children, become mentally ill as a result of living in imperialist-country cities, then that has a bearing on the principal contradiction within the u.$. white nation, which is in age. So, feelings and sentiments arising from contradictory parasitic life in imperialist metropoles both help and hinder the overthrow of imperialism.

How Trevor Reznik could develop angst even without feeling guilty about his hit-and-run

"The Machinist" may imply that the typical u.$. white worker is an exploited worker, so let's deal with this. Trevor Reznik is almost certainly an exploit er even though he rents his housing from a landlady and has bosses. According to an interview with director Brad Anderson, "The Machinist" is supposed to be set in Los Angeles, where the minimum wage is $6.25/hr.(5) To indulge MIM's critics, let's accept the language that u.$. workers are receiving "wages" and look at what Trevor's so-called wages would be. Even ignoring his nationality and even at the 10th percentile, or the lowest decile, Trevor could get $9.47/hr as a lathe operator in the united $tates, several times greater than the value of his labor taking into consideration the world market and adjusting for costs of living.(6) In November, 2003, the hourly mean wage of "lathe and turning machine tool setters, operators . . . " in "machine shops and threaded product manufacturing" was $14.59/hr. As a machinist, Trevor would get $9.91/hr at the lowest decile.(7) The November, 2003, hourly mean wage of machinists in "machine shops and threaded producted manufacturing" was $16.07/hr. Although, the November, 2003, median hourly wage of "lathe and turning machine tool settings, operators . . . " was $10.76/hr in the Los Angeles-Long Beach, CA primary metropolitan statistical area.(8) Trevor would likely have been employed at the same company for at least five years according to recent values of the median years of tenure for workers in "primary metals and fabricated metal products" or "machinery manufacturing." Also, the 2002 incidence rate of "nonfatal occupational injuries" with "cases with job transfer or restriction" for "fabricated metal products" was 2.7 per 100 full-time workers for a year, compared with 2.3 for just u.$. "manufacturing" as a whole.(9)

Let's take a look at what Trevor's brief Mein Kampf might look like. Exploiter and gender oppressor Trevor, in order to make his privileges more palatable to himself, either denies or ignores that he has power over people who are exploited and oppressed. He might even think of himself as some kind of oppressed persyn. Regardless, he must rationalize continuing to live in capitalist society and engaging in only sub-reformist or reformist action at the most. At the same time, urban life makes him feel that he is powerless to change the world. Here, there is an irreconcilable contradiction between consciousness and objective reality that is difficult to overcome even for parasites who are revolutionaries since they must, consciously or subconsciously, still rationalize participating in capitalist society to some degree (or commit suicide). Urban, oppressor nation parasites must rationalize participating in a society in which they have obvious privileges compared with other people in the world, but still feel powerless.

In the u.$. context, how can the white Jane or John Doe defend the government of a country in which there are almost three million millionaires, and obvious inequality and power differences even within u.$. borders? The word "whipped" comes to mind, but since the vast majority of Euro-Amerikans are exploiters, what we have here is that contradiction between the real powerfulness of parasitic privileges, and seeming and actual powerlessness. Only the wealthiest can escape this contradiction since they do have the power to demolish skyscrapers and construct new ones, for example. For the wealthiest persyns, there is less of that contradiction between powerfulness, on the one hand, and seeming powerlessness and actual powerlessness. Actually, the wealthiest can only begin to escape the contradiction since they, too, live under circumstances not of their own choosing, but are often the greatest purveyors of the ideology of individualism.

From contradictory parasitic life to schizophrenia

There is the objectively existing contradiction of parasitic life in imperialist metropoles: the contradiction between the powerfulness of parasitic privileges, and seeming and actual powerlessness related to living among highly dynamic, but seemingly invincible, social forces in the city. There is also a corresponding contradictory and unstable ideological formation in the parasites' minds, unstable because the contradiction is irreconcilable. Where the schizophrenic-like tendencies come in is in the need to provide the unstable ideological formation with some balance or stability. What "The Machinist" reflects is this additional, schizophrenic-like formation in the cognitive processes of imperialist-country workers. In "The Machinist," Trevor either ignores, or hallucinates or otherwise misperceives objective reality. In the real world, this same ignorance and misperception mitigates imperialist-country workers' subjective experience of the contradiction of parasitic life in imperialist metropoles. Put simply, they deny objective reality—either the reality of their parasitic privileges, or the reality of their powerlessness at the level of lifestyle. This is so that they can feel thoroughly powerful or thoroughly powerless—either way, there is less dissonance in their thinking as a result of this misperception. Urban, oppressor-nation parasites who support exploitive labor-aristocracy demands as being progressive may have developed this kind of schizophrenia.

Or they hallucinate powerfulness, rather than deny their powerlessness. In "The Machinist," Trevor doesn't just imagine Marie. He imagines paying her to provide him with companionship when he could just ask her out. Maybe he enjoys the power that money gives him to influence Marie.

Or they lose sight of objective reality in a more general way—to the point where they can't even differentiate, for themselves, between their different kinds of misperception, like fantasies and illusions. In "The Machinist," the rapid shifting between the different types of misperception—hallucinations, fantasies, and so on—to the point where the distinctions between them are blurred and sometimes even absent, represents Trevor's stumbling blindness as he moves through objective reality. Trevor seems to recognize that objective reality exists (he claims to be perceiving real things), but his perceptions are mashed together, and he can't distinguish between his own dreams and his daydreaming.

The schizophrenic-like mental formation generated by the contradiction of parasitic life in imperialist metropoles opens up possibilities for subjectivist thinking and fascist-leaning sentiments, if not articulated fascist ideology. In "The Machinist," some of Trevor's coworkers are Black, for example, Jones (Reg E. Cathey). They are among Trevor's coworkers who turn against him after the accident severing Miller's arm. The shop foreman is non-European. Trevor, a Euro-Amerikan, eventually loses his job by his own fault, but sees conspiracy all around him.

Notes:

1. "The Machinist," 2004, movie trailer, from Apple Computer, Inc. Web site, http://www.apple.com/trailers/paramount_classics/the_machinist.html

2. "The Machinist," 2004, from Lee's Movie Info , cited 2004 November 29, http://www.leesmovieinfo.net/wbotitle.php?t=2776

3. "Revolutionary feminism," from MIM Web site, http://www.prisoncensorship.info/archive/etext/gender/

4. MCB52, 1995 June, "The Oppression of Children Under Patriarchy," http://www.prisoncensorship.info/archive/etext/mt/mt9child.html

5. "IGN Interviews Brad Anderson," 2004 October 21, from IGN FilmForce , http://filmforce.ign.com/articles/558/558706p1.html?fromint=1

6. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2004 November 24, "Occupational Employment and Wages, November 2003 : 51-4034 Lathe and Turning Machine Tool Setters, Operators, and Tenders, Metal and Plastic," from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Web site, http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes514034.htm

Also see:

"White proletarian myths," from MIM Web site, http://www.prisoncensorship.info/archive/etext/contemp/whitemyths/

7. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2004 November 24, "Occupational Employment and Wages, November 2003 : 51-4041 Machinists," from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Web site, http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes514041.htm

8. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2004 November 24, "November 2003 Metropolitan Area Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates : Los Angeles-Long Beach, CA PMSA," from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Web site, http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_4480.htm

9. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, "Table 1. Incidence rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses by industry and case types, 2002," from U.S. Department of Labor Occupational Safety & Health Administration Web site, cited 2004 November 29, http://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/os/ostb1244.pdf