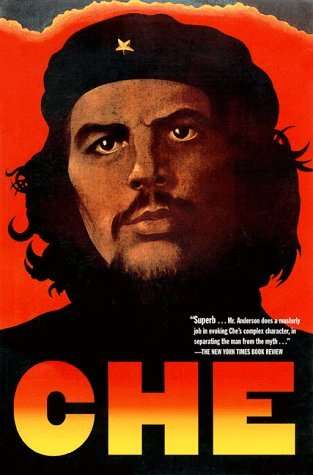

Book Review: Che Guevara, A Revolutionary Life

Che Guevara, A Revolutionary Life

by Jon Lee Anderson

Grove Press Books

1997

From de-classed aristocrat, to social vagabond, to communist revolutionary and legend, Che Guevara, A Revolutionary Life takes us from Che’s early beginning as a sickly kid with a tremendous appetite for reading to his miserable last days in the Bolivian mountains trying to spark a revolution. As far as biographies of political figures go this one is truly exceptional as Jon Lee Anderson does an outstanding job of focusing this book not on Che the individual but on Che the devoted servant of the people. There are just so many aspects and stages of Che’s life which this book covers that I already know I won’t have enough space to cover it all. Therefore I will stick to covering not so much what we already know about Che but what hasn’t yet been fully understood about him.

With that said, let us travel back in time to Argentina circa World War II, a country caught between Amerikan imperialism and a rising fascist influence. Ernesto “Che” Guevara was first turned on to politics as a young child through his friendships with several other children whose parents were Spanish migrants fleeing the Spanish Civil War. Che’s family was also apparently very active in Argentina’s petty bourgeois political circles. As a result of all these factors Che soon became semi-political himself, proudly joining the youth wing of Accion Argentina (Argentine Action), a pro-Allied solidarity group.(p. 23) However, he wouldn’t really begin developing a critical view of the world until his teenage years when he was shaped further by the political turmoil in his own country as well as by his Spanish émigré friends who had a measurable influence in his life. Years later they would all belong to local anti-fascist youth cells formed by Argentine students organizing against the militant youth wing of the pro-Nazi Alianza Libertadora Nacionalista (National Liberation Alliance).(p. 33) Besides this political organizing the rest of Che’s high school years were spent devouring every book he could get his hands on, including Karl Marx’s Das Kapital. Che later revealed to his second wife years later that at the time of reading Das Kapital he couldn’t understand a thing. Of course this would all change.

After graduating from high school he began to study philosophy, both inside and outside of college. He took engineering classes and enrolled in medical school. He also became fascinated with psychology. It was during this time that he began studying Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin. Yet during this time and the year that followed he continued to avoid any serious political participation. Paradoxically, however friends and family remember that Che began to debate politics with different organizations as well as with his family who were all very political, as if he was beginning to put his reading to the test.(p. 50)

During one of these discussions Che made his first anti-imperialist condemnation of the United $tates, accusing them of having imperial designs in Korea.(p. 50) It was not until his trips up and down South and Central America that Che Guevara would start to become radicalized. And it wasn’t books that did it, but “the injustice of the lives of the socially marginalized people he had befriended along his journeys.”(p. 63) It was also during this time that Che’s criticism and hatred for the United $tates began to grow, as now more than at any prior time in his life he was convinced that it was Amerikan imperialism that was the root cause of all of Latin@ America’s problems.(p. 63)

Through subsequent trips up and down the Americas Che met various Marxist intellectuals he had a high opinion of because they were “revolutionary.”(p. 118) In addition, he began to openly identify with a political cause, aligning himself and working within the leftist government of Arbenz in Guatemala. Also, very interesting to note that during this time Che began an ambitious project to write what would have been his first book titled The Role of the Doctor in Latin America(p. 135), a project he would unfortunately never finish due to his preoccupation with other revolutionary activities. A shame too as the ideas outlined for his book apparently dealt with the role of doctors during times of revolution, and one can’t help but draw parallels with Frantz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth written after, but around the same period of revolutionary upsurge in the Third World. Wretched not only deals with the anti-colonial struggle in Africa, but the role of the revolutionary psychiatrist.

As part of his preparation for this book, Che found it necessary “to take his knowledge of Marxism further, as he deepened his struggle of Marx, Engels, Lenin and the Peruvian Jose Carlos Marategui”(p. 136) founder of the Peruvian Communist Party which decades later would develop the Maoist Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path). He also discovered Mao Zedong and read about the Chinese communist revolution, ascertaining that their road to socialism had been different than the Soviet Union’s.(p. 136) Guevara’s resolve as a revolutionary would only become steeled in the ensuing chaos that followed the CIA-backed coup against the Arbenz government. This is also when the CIA first took notice of Che starting “one of the thickest (files) in the CIA’s global records.”(p. 159)

After Guatemala, Che fled to Mexico where his political destiny would become sealed after meeting the leaders of the July 26th Movement after their failed focoist attack on a Cuban military base. The leaders were Fidel and Raul Castro. Soon thereafter, the trio, along with a band of other Cuban exiles, left Mexico and began their historic guerrilla war against the Batista dictatorship. Their point of unification was that “Batista was little more than a pimp, selling off their country to degenerate foreigners…”(p. 170) But physical training and marksmanship wasn’t enough for Che in preparation to liberate Cuba. Confident that the revolution would succeed, Che intensified “his study of economics, he embarked on a cram course of books by Adam Smith, Keynes and other economists, boned up on Mao and Soviet texts…”(p. 189) Once in the Sierra Maestra Che kept up his studies as he wanted to have a firm grasp of political and economic theory.(p. 189)

After exhibiting exemplary fighting and leadership skills Fidel made Che his “chief of staff.” After the guerrilla victory, and among many other accomplishments and activities, Che concentrated on consolidating the initial revolutionary power base – the new Cuban military. Like Mao, Che sought to “raise the cultural level of the army.” In addition to basic literacy and education, the new military academy under Che was designed to impart political awareness to the troops.(p. 384) He even helped start Verde Olivio (Olive Green), a newspaper for the revolutionary armed forces.(p. 385)

Che was also made President of Cuba’s National Bank. Indeed, Che Guevara was fully immersed in trying to build up Cuba’s independent socialist economy. He recognized that in order to completely liberate itself from imperialist dependency, the Cuban economy would have to break free from the sugar industry which subsumed Cuba, turning it into a one-crop fiefdom. Cuba would also have to industrialize. Che was also for agrarian reform believing that the peasants who worked the land should have more control and reap more from it. Fidel had similar ideas on agrarian reform but not as far reaching as Che’s. As a matter of fact, a thorn of contention between Che and Fidel was Che’s strong belief that in order to succeed as a free and independent socialist state, Cuba would have to develop its own productive forces and should bow to no one, while Fidel preferred to play various imperialist powers off of one another in order to receive assistance in modernization and military equipment. And while Che would ultimately, though not always, come to echo Fidel’s line on modernization, this seemed to be more because of Che’s position as a head of state and diplomat.

To Che’s credit however he was the principal architect in designing Cuba’s economy and re-arranging the military prior to the Soviet Union’s involvement on the island. Many just don’t realize how much influence and power Che had in Cuba and that the creation of the many progressive institutions in Cuba can be directly attributed to Che’s influence on Fidel and Raul. And while Fidel would name Raul as his political successor, it was Che that many noted as Fidel’s true right-hand man despite his not even being a native Cuban.

One also gets the sense from reading this book that after the initial seizure of power, and as the political situation worsened for Cuba on an international level, Fidel trusted no one else in certain situations and so he ceded many matters of domestic and foreign policy to Che who had a better grasp of political economy, diplomacy and military affairs. This was the period in which the USSR, which had already taken the capitalist road, began to take notice of Che, not only because of his influence, but because of his strong peasant leanings and independent initiative, for which they would begin labeling him pejoratively as a “radical Maoist.” Che denied being a Maoist, but actions speak louder than words.

According to this book Che made two major criticisms of the Chinese Communist Party. The first was in accusing China of playing hardball with their rice for sugar assistance, accusing China of trying to starve Cuba. The second criticism was in berating China for not doing more to aid the Vietnamese in their struggle against Amerikan imperialism. Besides these criticisms it was very well known that Che had a high degree of unity with China which he very much revered for having a “higher socialist morality” than the Soviets, who he would increasingly and with frequency severely criticize over the remainder of his life. Among other things Che criticized the Communist Party of the Soviet Union for their bourgeois lifestyles which he witnessed first hand. More importantly, he later publicly condemned the Soviet Union for what he deemed collusion against Cuba with the United $tates. Later Che would hold up China’s socialist revolution “as an example that has revealed a new road for the Americas.”(p. 490) Furthermore, after returning from one of his trips to China, Che was “invigorated” with a new sense and deepened understanding of socialism, replicating some of China’s volunteer work brigades. He called these programs “emulacion comunista” (communist emulation).(p. 503)

Nearing his departure from Cuba for the last time Che began two more books which like Role of the Doctor he never finished: Philosophical Notes and Economic Notes. The latter being an extended critique of the Soviet Manual of Political Economy. On the eve of his final trek into the Bolivian mountains he sent an outline of the text to the budgetary finance system (BFS) for review indicating that he was ready to put his anti-Soviet line on political economy into practice (Guevara was the head of the BFS). According to the author, what Che had in mind was “a new manual on political economy better applied to modern times, for use by developing nations and revolutionary societies in the Third World.”(p. 696) Furthermore, according to Anderson who interviewed former members of the BFS who read Che’s critique, Che wrote in the manual that the USSR and the Eastern Bloc were doomed to return to capitalism if they didn’t reform their economies.”(p. 697) Apparently these documents were left to a comrade who never found the time to push for publication in the increasingly social imperialist dominated Cuba. Today they remain in Cuba locked away along with other of Che’s documents, which Fidel deemed too sensitive to publish.(p. 697)

In the end and throughout his career it is very well known that Che was a focoist and was killed because of his ultra-left and idealized version of what a popular war looked like. Yet I was surprised to find out that Che’s war strategy for Latin@ America was somewhat similar to Mao Zedong and Lin Bao’s conception of global “Peoples War” for the Third World. As Che pointed out in Guerrilla Warfare: A Method, the liberation of the Americas from Amerikan hegemony could only come about through a virtual united front of guerrilla and other peasant forces that would use the Andean mountains which stretch from the top of South America to the bottom as a series of revolutionary base areas which they would use to attack the cities and urban zones of Latin@ American countries, slowly but surely wresting control of one country after another until all of Latin@ America was free. This is akin to the village-encircle-city strategy of Lin and Mao.

The story of Che Guevara and his iconic image has not yet been forgotten by revolutionaries today, as it continues to inspire us in our own struggles. It is truly a pity that Che succumbed to his focoist beliefs. His story should not only serve as an example as to the type of revolutionaries we should aspire to become, but should also serve as an example of what can happen if we pick up the gun too soon. Focoism has taken away too many good comrades, and in Che Guevara it took away a great comrade! Let it not take one more. So on this day the forty-seventh anniversary of the death of Che Guevara, (9 October 2014) and the day commemorating and honoring Che, “The Day of the Heroic Guerrilla” (8 October 2014) let us raise the red banner of revolution just as Che continuously raised it and died holding it. Let us raise the red banner for the proletariat, for our lumpen and for our nations! Let us be like Che! Seremos Como el Che!