Bromma's Worker Elite and the Global Class Analysis

The Worker Elite: Notes on the “Labor Aristocracy”

by Bromma

Kersplebedeb, 2014Available for $10 + shipping/handling from:

kersplebedeb

CP 63560, CCCP Van Horne

Montreal, Quebec

Canada

H3W 3H8

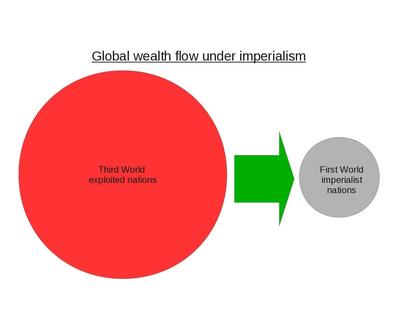

As with our previous review of Bromma’s writings, we find h new book to be a good read, based in an analysis that is close to our own. Yet, once again we find h putting class as principal and mentioning gender as an important component of class. In contrast, MIM(Prisons) sees the principal contradiction under imperialism as being along the lines of nation, in particular between the imperialist nations that exploit and those nations that are exploited. While all three strands interact with each other, we see gender as its own strand of oppression, distinct from class. While Bromma has much to say on class that is agreeable, one thread that emerges in this text that we take issue with is that of the First World labor aristocracy losing out due to “globalization.”

Bromma opens with some definitions and a valid criticism of the term “working class.” While using many Marxist terms, h connection to a Marxist framework is not made clear. S/he consciously writes about the “worker elite,” while disposing of the term “labor aristocracy” with no explanation. In the opening s/he rhetorically asks whether the “working class” includes all wage earners, or all manual laborers. While dismissing the term “working class” as too general, Bromma does not address these questions in h discussion of the worker elite. Yet, throughout the book s/he addresses various forms of productive labor in h examples of worker elite. S/he says that the worker elite is just one of many groups that make up the so-called “middle class.” But it is not clear how Bromma distinguishes the worker elite from the other middle classes, except that they are found in “working class jobs.” Halfway through the book it is mentioned that s/he does not consider “professionals, shopkeepers, administrators, small farmers, businesspeople, intellectuals, etc.” to be workers.(p.32)

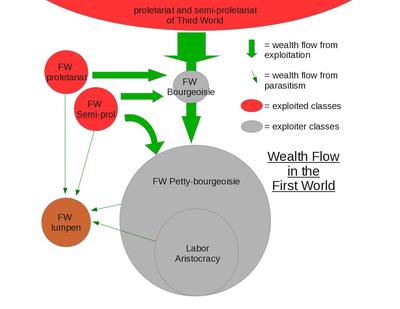

We prefer the term “labor aristocracy” over “worker elite,” and we may use it more broadly than Bromma’s worker elite in that the type of work is not so important so much as the pay and benefits. Bromma, while putting the worker elite in the “middle class,” simultaneously puts it into the “working class” along with the proletariat and the lumpen working class. We put the labor aristocracy in the First World within the petty bourgeoisie, which may be a rough equivalent of what Bromma calls the “middle class.” Of course, the petty bourgeoisie has historically been looked at as a wavering force between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. Yet, in the case of the oppressor nation labor aristocracy, they have proven to be a solidly pro-imperialist class. This analysis, central to MIM Thought, is particular to the imperialist countries.

Despite these questions and confusions, overall we agree with the global class analysis as it is presented in the beginning of this book in terms of who are our friends and who are our enemies.

One good point made throughout this book is the idea that the “worker elite” is not defined merely by an income cut off. While not denying the central role of income, Bromma defines this class position as a whole package of benefits, material (health care, infrastructure), social (family life, leisure activities) and political (lack of repression, voice in politics). At one point s/he brings up the migrant farm workers in the U.$., who can earn similar amounts to the autoworkers in Mexico who s/he argues make up an established worker elite. In contrast, the migrant farm workers suffer the abuses of the proletariat at the bottom rung of U.$. society, and in reality many make far less than Mexican autoworkers. We agree with Bromma’s implication here that the migrant workers make up a proletarian class within the United $tates.

While criticizing previous attempts to set an “exploitation line” in income, Bromma brings in PPP to improve this analysis. The book provides a helpful table of the income levels in Purchasing Power Parities (PPP) for various groups. PPP defines income levels relative to a basket of goods to account for varying prices across countries/regions. Bromma concludes that “a global middle class annual income probably starts somewhere between PPP $10,000 and $15,000”, meaning that a single worker (man) could comfortably support a family on this amount. This is similar to the estimates others have done and we have used elsewhere.

One of the key characteristics of this income level is that they have gone beyond covering basic needs and become consumers. Bromma lists one of the three main roles of the worker elite as being a consumer class. This is something we have stressed when people ask incredulously why the capitalists would pay people more than the value that they are producing. Bromma cites a source discussing the Chinese planned capitalist economy and how they have goals for expanding their consumer class as they recognize that their increasing production will soon not be absorbed by consumption abroad. This is typical capitalist logic. Rather than seeing what the Chinese people need, and produce based on those needs as they did under a socialist planned economy, today they first produce a lot of the most profitable goods and then try to find (or create) a market to sell them to.

Where we disagree greatest with this book is that it takes up a line akin to Huey P. Newton’s intercommunalism theory, later named globalization theory in Amerikan academia. It claims a trend towards equalization of classes internationally, reducing the national contradictions that defined the 20th century. Bromma provides little evidence of this happening besides anecdotal examples of jobs moving oversees. Yet s/he claims, “Among ‘white’ workers, real wages are stagnant, unemployment is high, unions are dwindling, and social benefits and protective regulations are evaporating.”(p.43) These are all common cries of white nationalists that the MIM camp and others have been debating for decades.(1) The fact that wages are not going up as fast as inflation has little importance to the consumer class who knows that their wealth is far above the world’s majority and whose buying power has increased greatly in recent decades.(2) Unemployment in the United $tates averaged 5.9% in April 2014 when this book came out, which means the white unemployment rate was even lower than that.(3) That is on the low side of average over the last 40 years and there is no upward trend in unemployment in the United $tates, so that claim is just factually incorrect. High unemployment rates would be 35% in Afghanistan, or 46% in Nepal. The author implies that unions are smaller because of some kind of violent repression, rather than because of structural changes in the economy and the privileged conditions of the labor aristocracy.

The strongest evidence given for a rise in the worker elite is in China. One report cited claims that China is rivaling the U.$. to have the largest “middle class” soon.(p.38) Yet this middle class is not as wealthy as the Amerikan one, and is currently only 12-15% of the population.(p.32) It’s important to distinguish that China is an emerging imperialist power, not just any old Third World country. Another example given is Brazil, which also has a growing finance capital export sector according to this book, a defining characteristic of imperialism. The importance of nation in the imperialist system is therefore demonstrated here in the rise of the labor aristocracy in these countries. And it should be noted that there is a finite amount of labor power to exploit in the world. The surplus value that Chinese and Brazilian finance capital is finding abroad, and using partly to fund their own emerging consumer classes, will eat into the surplus value currently taken in by the First World countries. In this way we see imperialist competition, and of course proletarian revolution, playing bigger roles in threatening the current privileges of the First World, rather than the globalization of finance capital that Bromma points to.

As Zak Cope wrote in a recent paper, “Understanding how the ‘labour aristocracy’ is formed means understanding imperialism, and conversely.”(4) It is not the U.$. imperialists building up the labor aristocracy in China and Brazil. South Korea, another country discussed, is another story, that benefits as a token of U.$. imperialism in a half-century long battle against the Korean peoples’ struggle for independence from imperialism and exploitation. While Bromma brings together some interesting information, we don’t agree with h conclusion that imperialism is “gradually detaching itself from the model of privileged ‘home countries’ altogether.”(p.40) We would interpret it as evidence of emerging imperialist nations and existing powers imposing strategic influence. Cope, building on Arghiri Emmanuel’s work, discusses the dialectical relationship between increasing wages and increasing the productive forces within a nation.(2,5) Applying their theories, for Chinese finance capital to lead China to become a powerful imperialist country, we would expect to see the development of a labor aristocracy there as Bromma indicates is happening. This is a distinct phenomenon from the imperialists buying off sections of workers in other countries to divide the proletariat. That’s not to say this does not happen, but we would expect to see this on a more tactical level that would not produce large shifts in the global balance of forces.

Finance capital wants to be free to dominate the whole world. As such it appears to be transnational. Yet, it requires a home base, a state, with strong military might to back it up. How else could it keep accumulating all the wealth around the world as the majority of the people suffer? Chinese finance capital is at a disadvantage, as it must fight much harder than the more established imperialist powers to get what it perceives to be its fair share. And while its development is due in no small part to cooperation with Amerikan finance capital, this is secondary to their competitive relationship. This is why we see Amerika in both China’s and Russia’s back yards making territorial threats in recent days (in the South China Sea and Ukraine respectively). At first, just getting access to Chinese labor after crushing socialism in 1976 was a great boon to the Amerikan imperialists. But they are not going to stop there. Russia and China encompass a vast segment of the globe where the Amerikans and their partners do not have control. As Lenin said one hundred years ago, imperialism marks the age of a divided world based on monopolies. Those divisions will shift, but throughout this period the whole world will be divided between different imperialist camps (and socialist camps as they emerge). And as Cope stresses, this leads to a divided “international working class.”

While there is probably a labor aristocracy in all countries, its role and importance varies greatly. MIM line on the labor aristocracy has been developed for the imperialist countries, where the labor aristocracy encompasses the wage-earning citizens as a whole. While the term may appropriately be used in Third World countries, we would not equate the two groups. The wage earners of the world have been so divided that MIM began referring to those in the First World as so-called “workers.” So we do not put the labor aristocracy of the First World within the proletarian class as Bromma does.

We caution against going too far with applying our class definitions and

analysis globally. In recent years, we have distinguished the First

World lumpen class from that of the lumpen-proletariat of the Third

World. In defining the lumpen, Bromma “includes working class people

recruited into the repressive apparatus of the state – police,

informants, prison guards, career soldiers, mercenaries, etc.”(p.5) This

statement rings more true in the Third World, yet even there a

government job would by definition exclude you from being in the

lumpen-proletariat. In the imperialist countries, police, prison guards,

military and any other government employee are clearly members of the

labor aristocracy. This is a point we will explore in much greater

detail in future work.

The principal contradiction within imperialism is between exploiter and exploited nations. Arghiri Emmanuel wrote about the national interest, criticizing those who still view nationalism as a bourgeois phenomenon as stuck in the past. After WWII the world saw nationalism rise as an anti-colonial force. In Algeria, Emmanuel points out, the national bourgeoisie and Algerian labor aristocracy had nothing to lose in the independence struggle as long as it did not go socialist. In contrast, it was the French settlers in Algeria that violently opposed the liberation struggle as they had everything to lose.(6) In other words there was a qualitative difference between the Algerian labor aristocracy and the French settler labor aristocracy.

It is the responsibility of people on the ground to do a concrete analysis of their own conditions. We’ve already mentioned our use of the term “First World lumpen” to distinguish it from the lumpen of the Third World, which is a subclass of the proletariat. To an extent, all classes are different between the First and Third World. We rarely talk of the labor aristocracy in the Third World, because globally it is insignificant. It is up to comrades in Third World nations to assess the labor aristocracy in their country, which in many cases will not be made up of net-exploiters. Bromma highlights examples of exploiter workers in Mexico and South Korea. These are interesting exceptions to the rule that should be acknowledged and assessed, but we think Bromma goes too far in generalizing these examples as signs of a shift in the overall global class structure. While we consider Mexico to be a Third World exploited nation, it is a relatively wealthy country that Cope includes on the exploiter side, based on OECD data, in his major calculations.

Everything will not always fit into neat little boxes. But the scientific method is based on applying empirically tested laws, generalizations, percentages and probability. The world is not simple. In order to change it we must understand it the best we can. To understand it we must both base ourselves in the laws proven by those who came before us and assess the changes in our current situation to adjust our analysis accordingly.

Related Articles:This article referenced in: